In 2001, Samia Halaby independently published Liberation Art of Palestine, a detailed study of Palestinian art during the second half of the twentieth century. The first of its kind, Liberation Art is an English-language book that is based on dozens of interviews with artists who were integral to a movement that remains embedded in Palestinian visual culture. Halaby’s recognition of this specific school and her outlining of its creative parameters have been indispensable to the documentation of Palestinian art while indirectly providing a template for how the history of modern and contemporary Arab art should be considered—a history that has never been divorced from the political.

Beginning in the 1960s with a core group of politically committed artists, Liberation Art established a transnational art scene through which the revolutionary struggle against Israeli occupation could take on a visual component. Its artists projected images of defiance, resistance, and cultural pride despite frequent incursions, the severity of blockades, and a growing exilic condition. With iconic symbolism, Liberation Art provided a compelling medium for the Palestinian narrative, widening the scope of its cultural participation in the international sphere. Today, as Palestinians reinvent the ways in which their collective experience is understood with equal resonance, traces of the movement can still be found in the work of young artists.

Many of the Liberation artists continue to be active, especially Halaby whose recent monograph Five Decades of Painting and Innovation (Ayyam Publishing) confirms the many contributions to abstract art that have resulted from her long career. Born in Jerusalem in 1936, Halaby relocated to the US in 1951 from Lebanon, where her family sought refuge during the Nakba. Receiving her formal training from American universities and based in New York since 1976, she was the first fulltime female associate professor at the Yale School of Art, a position she held for nearly a decade. Her work is housed in public and private collections throughout the world, including the Guggenheim Museum of Art (New York and Abu Dhabi) and The British Museum. Coinciding with her scholarship on Palestinian art have been a number of seminal exhibitions that she has either curated or helped organize, most notably “The Subject of Palestine” (DePaul Art Museum, 2004), “Made in Palestine” (The Station Museum, 2002), and “Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World” (the National Museum for Women in the Arts, 1994). The forthcoming book, Jerusalem Interrupted: Modernity and Colonial Transformation 1917-Present (ed. Lena Jayyusi, Olive Branch Press) will feature a chapter by Halaby titled “The Pictorial Arts of Jerusalem During the First Half of the 20th Century.”

Maymanah Farhat (MF): What was the original inspiration for your book Liberation Art of Palestine?

Samia Halaby (SH): It started in the 1990s when I began to visit Palestine a lot. I met with artists of the revolution and put the resulting interviews on my web page. The urge for all this really had something to do with my great friendship with leading Arab sculptor Mona Saudi. I had first met her in 1979 during a visit to Beirut. I listened intently to her discussions of the work that she did for the Plastic Arts Section of the Palestine Liberation Organization. She invited me to be in an exhibition at the Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo in 1981 and there I met a lot of resistance artists from Beirut and the Arab world, most of who were Palestinian.

MF: Mona was head of the Plastic Arts Section of the PLO at one time—a role that was traditionally filled by artists who were active in the Palestinian struggle, including the late painter Ismail Shammout, its founding director. How important was this position to the Palestinian art scene in the 1960s and 70s, or more specifically to the development of Liberation Art?

SH: Arafat had the habit of keeping the people under him in competition with each other, and not with him, by creating doubles of many things. Thus while Ismail Shammout and his wife, painter Tamam al-Akhal, led the Arts and Heritage Section of the PLO; Mona Saudi led the Plastic Arts Section. She was active and her commitment to the Palestinian cause during the 1970s and 80s was deeper than most artists. However, others, like Ismail Shammout, stayed the course.

[Mona Saudi, “Dawn” (1986).]

MF: In the mid 1960s, you returned to Palestine for the first time since being exiled in 1948. You’ve discussed this before as a formative trip for you, both in terms of your own art and a sort of revisiting of the visual culture of Palestine that impacted you as a child—namely the architecture, decorative arts, and religious imagery that seems to be essential to Palestinian life. During this trip, you also met with the pioneering painter Sophia Halaby, a distant relative of yours, whose landscapes were crucial to the development of Palestinian painting in the first part of the twentieth century. You include her in your study of Liberation Art. How, if at all, did your experience as a young painter returning to Palestine shape your understanding of Palestinian art?

SH: In terms of facts, it was really an experience of discovery. In terms of essence, it was a visit to familiar realms. One of my recurring thoughts is in relation to the kind of art that I was making independently while in undergraduate school. Once I entered graduate school at Indiana University my professors fought it out of me. While an undergraduate, I did not fight my professors. I listened and learned and did my thing outside of class. But by graduate school, my independent work had developed and they had a tough job weeding it—yet they did so. I am not sure it was a bad thing, as we always grow and learn. But when I went back to Palestine in 1966 and began to travel to Lebanon in the late 1970s (and more frequently to Palestine in the 90s), I realized that what I had developed independently while an undergraduate and what was later weeded out of me looked very much like a lot of the work of Palestinian artists. Later, I also observed that when I curated the exhibition “The Subject of Palestine” at the DePaul Art Museum in 2004 and had to pass artwork by the director, there was no way that I could get her to think positively of the work of Abdel Rahmen al-Mozayen, whom she thought was ”stylized.” She hated it. While her dislike was hard for her to explain, it reflected her intuitive class antagonism.

[Abdel Rahmen al-Mozayen, “Intifada: Against Fascism” (1988).]

MF: When did it become clear to you that there was a twentieth-century movement that could be classified as “Liberation Art”?

SH: It was really clear before I began to work on the book in earnest. I had my web page by 1994 and posted some interviews with artists of the movement on it between 1994 and 1999. But I became sure as my interviews with artists progressed and as I learned and saw more. I asked many artists about what they admired or hated. Within the twentieth century, they admired the Cubists and the Mexican Muralists most of all. I began to see that the movement was one of the more progressive of the century, the last one in fact. It fit into my analysis that international painting in the twentieth century sea-sawed between advances and regressions based on revolutionary progress or defeat. I saw the Liberation Art movement as the final one in a succession beginning with Cubism, followed by Futurism (in its many flavors), then by Constructivism and Suprematism, and later the Mexican Muralists and Abstract Expressionism. This series finally asserted itself in the Liberation Art of Palestine.

MF: The show in Oslo, although somewhat obscure, included artists whom you identify as leaders of Liberation Art such as Abdel Rahmen al-Mozayen, Sliman Mansour, and the late Mustafa Hallaj. Was this your first time exhibiting with your fellow Palestinian artists against the backdrop of political struggle and within the framework of Liberation Art?

SH: I had exhibited with them a little bit but it was the first substantial show as a group and it was the first time that I met the others together in a foreign country, which tended to push us closer. There were also artists from the Arab world who were not Palestinian. For example, there was Mohammed Hajras from Egypt who did Cubist sculpture. The uprising in Beirut brought supporters from all over the world. There was a German artist, who adopted the name Jihad Mansour. He was not in the show but was loved. In 1990 Abdul Hay Al Musallam did a bas-relief in his honor on hearing that he was imprisoned in Germany. I remember that at the Oslo show they had appointed me as their spokesperson to the press, as Mona was delayed by the war in Lebanon. Sliman Mansour, of course, was not able to come. One of the tragedies of the Liberation movement was how difficult it was for artists on Palestinian soil to be able to travel and meet those in exile. Israel imposed some huge and frightening limitations. They were constantly under attack. Their work often confiscated and their exhibitions often burnt or closed.

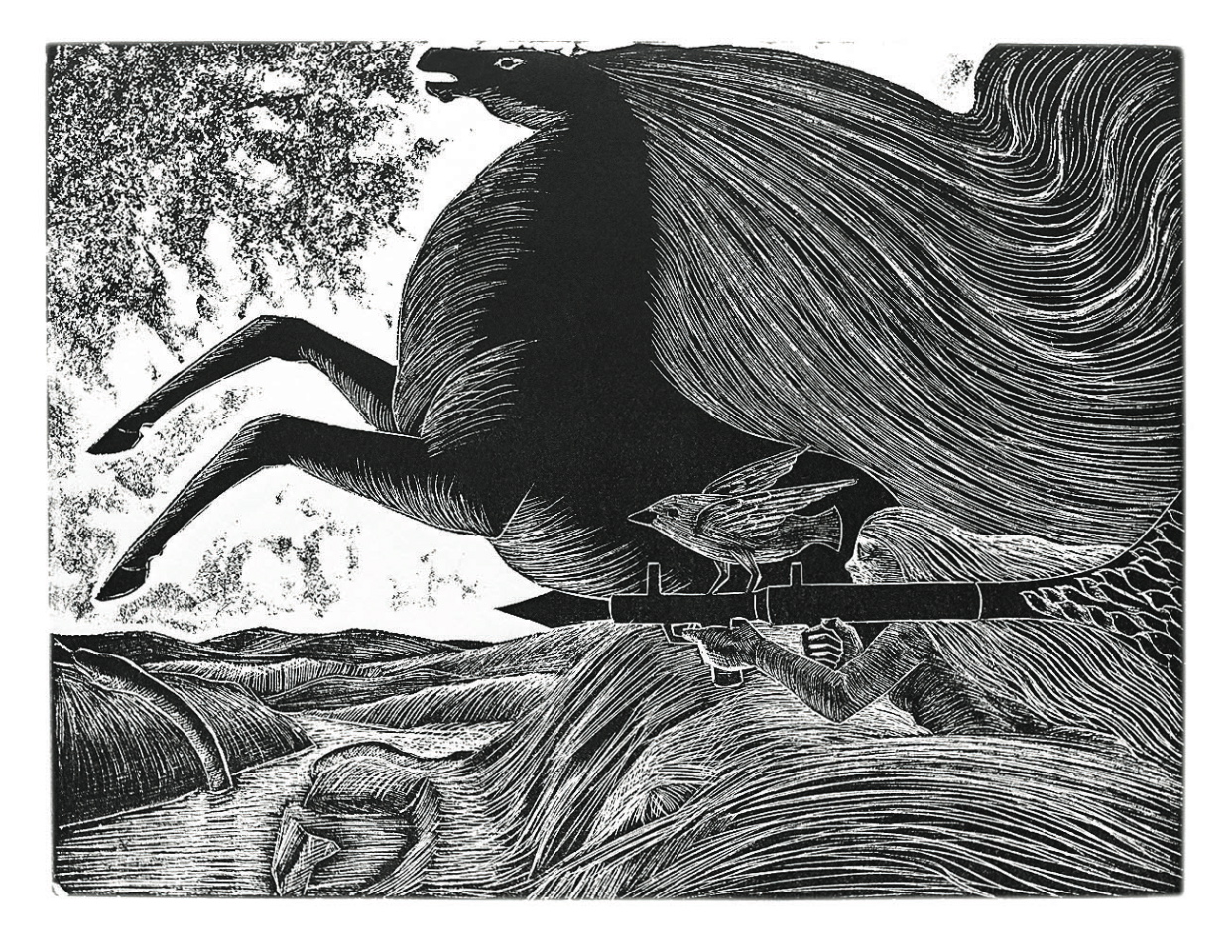

[Mustafa Hallaj, “The Battle of Al Karameh” (1969).]

MF: Do you recall how the exhibition came about?

SH: It came about as an idea of artists in Oslo. Although the Kunstnernes Hus had professional arts administrators, it had a rather important artists’ committee, which really oversaw the museum. This is what was told to me by the Norwegian artists who I met there, who initially thought that it would be interesting to know how art might thrive or exist under conditions of war. They then got in touch with the PLO and from there with Mona Saudi. Mona was super active at the time, organizing international exhibitions and gathering some big names to shows. Thus it was she who organized and pushed for the show in Oslo. The catalog had an introductory comment by Yasser Arafat.

MF: Was Mona connected with the museum for Palestine in Beirut that was bombed by Israeli forces during the Lebanese Civil War? How was that museum created? Who was responsible for drawing in world-renowned artists, such as Joan Miro, to its collection? How was the museum connected to the happenings of the Liberation Art movement?

SH: It was called the Museum of Solidarity with Palestine. The Israelis bombed it in 1982 and turned its contents to rubble. It was the work of Mona Saudi and part of her Plastic Arts Section of the PLO. She was the moving spirit and it is she who traveled and brought contributions from important international artists. When the museum was under Israeli bombardment, Mona and her sister Fathiyye put their lives at risk to rescue the artwork by car and distributed it to private homes so that it would be safe. I had two drawings of our great thinker and leader, the martyred writer Ghassan Kanafani, at the museum. I thought that they had probably been bombed to shreds. But in time I discovered that one of them, the better one, survived and is hanging in his wife’s home in Beirut. I immediately said that it must remain there.

MF: Was the PLO involved in promoting Palestinian art as part of their cultural policy or were such exhibitions more the work of a strong network of like-minded artists who merged political activism and art? Were there other organizations or offshoots of the PLO that were involved in forging the art scene?

SH: Artists pushed the PLO from below, initiating and maintaining its involvement. Within the organization there were several arts and cultural sections, including film and photography. Once the impetus from the artists was felt, the PLO took it up formally and supported these sections financially. The political groups were also keen to claim the artists as their own. No government and its official parties ever loved its artists as much. Many international shows in the “Socialist Block” were organized. I know for example that there was an important show in the former Soviet Union in which my work was included. I gave a batch of artwork to Mona who then sent it to shows. The majority of international shows during this time were organized by sections of the PLO—that is by Ismail Shammout or Mona Saudi and they were competitors in this. Then when the movement went to the West Bank, the Rabita, the union of Palestinian artists inside, began to organize such shows as well. Sliman Mansour organized a great deal of them. As the years went by, and the revolution waned, he began to concentrate on showing his own work and that of his close network. But it is important to remember Sliman’s great contributions. During the very early days of the revolution, immediately after the 1967 war when borders between the West Bank and Palestine48 (parts occupied in 1948) opened, Sliman traveled to towns and villages inside the green line to connect with artists and youth while introducing them to art of the uprising. He traveled abroad and gave slide shows of Liberation Art. Attending one of his presentations in the 1970s energized me. He is an important artist.

There were a host of informal organizations, all very loose and liquid. In each city of the Arab world there was a union of Palestinian artists and a literary group as well. There was an international meeting of these groups in Lebanon during the revolution. In 1971 Ismail Shammout was elected president of both the Union of Palestinian Artists and the Union of Arab Artists. He was a primary leader in the first meeting of the Union of Palestinian Artists in 1979. The Liberation artists in Beirut and in the West Bank organized galleries, rented spaces, and actively exhibited painting (occasionally sculpture).

MF: At that time, and specifically within the context of Palestine, were the two, i.e. political activism and art, ever really separate? Of course in the example of Abdel Rahmen al-Mozayen, who was a resistance fighter and, like Ismail Shammout, designed many of the PLO’s political posters, there was obviously no separation.

SH: No not really. But one cannot say that about each and every artist. In general, however, it was the enthusiasm of the revolution that bore up the artists and moved them to collective action. Most of them were enthusiastic but some were not. In Lebanon there were a few Palestinian artists who did not connect with the movement. Otherwise, I would say that among most Palestinian artists political activism and art generally merged.

MF: How and when did your formal research on Palestinian art begin?

SH: My curiosity and knowledge about Palestinian artists in Beirut began in the late 1970s. However, I had no idea that the artists of the revolution were as substantial as I later found when traveling to Palestine in the 1990s. In 1999, Sliman Mansour, who was then the head of the Wasiti Art Center, asked me to write a 40-page essay on Palestinian art after seeing my interest in artists. I accepted. I submitted my manuscript to him and he felt it was too long. He ended up editing it with a heavy hand so I pulled it from him and worked on it, seeking advice from many colleagues. It would have probably been a secret project on which I would have worked for ten more years were it not for a graphic designer friend who needed work and pushed me. I should thank her for that. Research began in earnest after talking to Sliman Mansour, who suggested that I rent a car and drive inside the green line to Palestine 48, the Israeli entity, in 1999. I was scared but Sliman encouraged me. I called artists whose numbers he had given me and met and interviewed them. I made great friendships. When inside the green line both sides (those exiled and those living inside) immediately feel that we have to pack a lifetime of acquaintanceship into a few hours. A great empathy results. In the end, I interviewed forty-six artists before starting the book. I also collected and read any and all printed material that I could find. I saw Kamal Boullata’s book before I had finished my research and I read the parts that pertained to my focus. His intention in his Arabic text, Istihdar Al Makan, (published by the Arab League’s Educational, Cultural, and Scientific Organization) is very different from mine. I wanted to pursue an art historical tradition by not only analyzing what I had discovered in my field research but by seeing how it fits into an international historical context.

[Sliman Mansour, “I, Ismael” (1997). Collection of Naim Farhat.]

MF: What are the major components of Liberation Art? What are some of the most prevalent characteristics of the movement? Techniques? Mediums? Imagery?

SH: Liberation artists initially worked in a variety of mediums—painting, sculpture, printmaking, etc. The artists of the revolution wanted their work in every home and refugee tent. Thus they all made art posters for distribution. Then there came a time during the Intifada when artists wanted to boycott Israeli art supplies and it pushed them to discover materials out of their own backyard. Painter Nabil Anani went to Al-Khalil (Hebron), found leather tanners, and began working with leather. The leather could not be stretched onto big canvases so he made small pieces that fit together like a puzzle. He exploited the pieces as shapes in an image. Painter Tayseer Barakat used a method known as pyrography, the art of creating images by burning, on pieces of wood that he made separately then assembled. Ceramists Vera Tamari and Mahmoud Taha made individual pieces of clay—coloring them first then firing them. They would then assemble them to create an image that had a free edge, not a rectangular one. This method of assembling pieces that Anani, Barakat, Taha, and Tamari used was indebted to the methods of traditional inlays one sees in Arabic (Islamic) geometric abstraction, in wood inlays and mother-of-pearl boxes, and in stained glass.

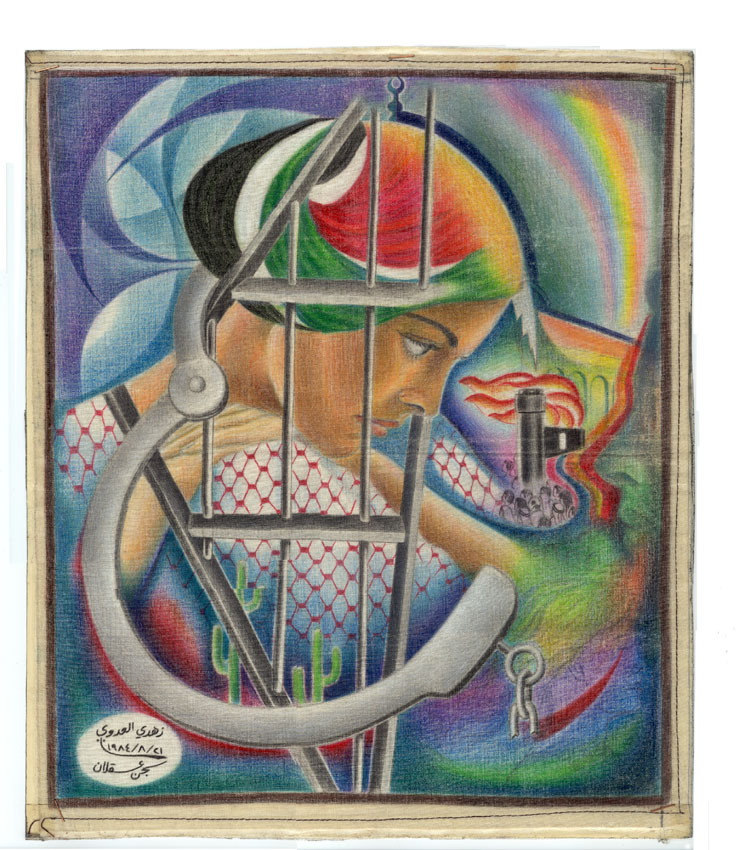

Liberation Art is symbolist, using images of things known to popular Palestinian culture – things that anyone experiencing Palestinian life could identify. The horse came to mean revolution. The flute came to mean the tune of the ongoing resistance. The wedding came to mean the entire Palestinian cause. The key came to mean the right of return. The sun came to mean freedom. The gun with a dove came to mean that peace would come after the struggle for liberation. Artists used the colors of the flag, patterns from embroidery, chains, etc. Village scenes, village dress, the prisoner, prison bars. There were special themes regarding the martyr. First there were generalized pictures of the martyr as well as pictures of specific individuals who had been killed by the Israelis. The second form was based on a popular practice of framing a collage of symbols representing the deceased’s life then hanging it at their home or grave.

Artists unanimously wanted to avoid Western art. In an interview for my research, Nabil Anani pointedly stated that he rejects perspective and shading. They wanted to be revolutionary and international but based on the history of Arabic and ancient arts of the area. Tayseer Barakat pointed out his debt to ancient Assyrian, Sumerian, and Egyptian art, as did Mustafa Hallaj. They considered that they had a cause and that serving that cause was far more important than any other way of painting. Uncommitted art was to them anathema. As the revolutionary spirit waned, the movement no longer buoyed the artists and many changed their views.

I also noticed that the social upheaval, the spirit of revolution, energized them. The artists unionized, created discussion groups, founded galleries, and wrote about their efforts. They became activists and socially responsible. For example, Vera Tamari and other women organized a show of Palestinian women artists, honoring Sophia Halaby at the event. Artists tended to become more generous and cooperative during the uprising from the early 1970s to the early 90s. Ismail Shammout did his utmost to help other artists. The tendency was to encourage anyone who experimented in drawing and painting to do more. Often, they would be helped to gain an education or take short courses. Ismail Shammout wrote the first book featuring Liberation Art, which is full of pictures. Considering the general destruction that this art has undergone, that book is a precious document.

MF: This included untrained artists?

SH: Yes, anyone who did any drawing or painting was immediately encouraged to do more. Many artists of the movement never received academic art training, such as Abdel Hay al-Musallam and Fathi Ghaban. Some, not all, of those who had no formal training would excel and make great art during the movement, then get lost afterwards. That is not true of Musallam, however.

Another interesting fact about the effect of collective enthusiasm and the optimism of the movement can be seen clearly in the work of the two well-known prisoner artists. While in prison, both Zuhdi al-Adawi and Muhammad al-Rakoui were in daily communication with their fellow prisoners—indeed they shared cells in which a large number of fellow political prisoners lived. They received constant input and encouragement as well as criticism from other prisoners. They had no privacy; they worked in public, so to speak. The enthusiasm of the day led them to discover very creative methods of sneaking the work out past Israeli prison guards to anxiously awaiting supporters, who then organized exhibitions of their work. Unfortunately, once free and living in Damascus, they were both thrown out of the embrace of the revolution and their art suffered as a result. Their lack of art education manifested itself most clearly.

[Zuhdi al-Adawi, “Day of the Prisoner” (1984). ]

MF: As one of the Arab world’s leading abstract painters and someone who has long been committed to the struggle, how have you addressed the subject of Palestine in your own work?

SH: I remember a young Palestinian at one of my shows asking me “Where is Palestine in your paintings?” I wrote an essay in response essentially saying that one has to know the class interests of those asking the question, then respond accordingly. I think the student was sincere and I explained to him that there is political art and there is explorative art. I do political art that expresses my views in posters and banners and documentary art. But as an explorative painter I intend to seek to be the best international painter that I can be. There are Arab liberals and bureaucrats who support imperialism and want something Arabic or something Palestinian in art to support their pretenses but they do not want it too political or explicit. A bit of calligraphy usually satisfies them. Even Imperialism wants you to be true to your ‘roots’ so to speak. In this way they seek to categorize us, limit our ambitions and remove us from the international mainstream, which they see as belonging to them and their loyal supporters. One mature Palestinian artist, Yaser Dweik, kept arguing with me about all this but was finally persuaded when I told him to remember that if his ambition is high and he attains it, then it will be historically known that a Palestinian artist reached that height. But I do not object to Palestine in explorative abstract painting. It is often there in my paintings. The thing is, abstraction is not specific and in its general forms it applies to many specifics. Yet it is also important to remember that the tragedy of Palestine is not unique. Any number of African nations, nations in the sense of peoples not states, suffer worse treatment. The nations of the Americas have been treated in similar and more devastating ways.

MF: The phenomenon of artists taking on multiple roles and serving as curators, writers, critics, and organizers was something that was prevalent throughout the Arab world up until the 1990s. In your book you include your own work as part of the movement. It is only recently that such professional distinctions became part of the Arab art scene. Now there is an abundance of writers, curators, gallerists, and non-profit heads—many have been trained in these specializations. In a previous conversation you mentioned the underlying issues of class that are evident in this recent shift in art world professions in terms of the distribution of political and social agency within a given art scene, can you elaborate on this?

SH: Historically, as I study art, it seems to me that it is more often artists who are rejected by the arts establishment and that it is only some decades later that they seem to be recognized as the best of their times. You are probably right about it being the case not just in Palestine. But in the case of Palestine this new layer of bureaucrats is comprised of those who are often trained in the West, are indeed foreign nationals, or are financially supported by colonizers and imperialists. They tend to have ‘educated’ taste and a Western knowledge base. They tend to know nothing of international art history yet they have the power to impose their will. Artists need to live and in capitalist society only the gallery can bring them the sales they need to survive. So those who have the money set the tone.

MF: This onset of a gallery-driven art scene seems foreign to the Arab world, especially after decades of artists having to act as their own advocates. On the one hand it is nice to see a number of artists receive their just deserves and recognition, especially those who have contributed to the regional art scene for so long. Paradoxically, however, as it becomes commercially driven, the art scene becomes oversaturated with one-liners, generating an endless supply of artists who get caught in creative ruts due to the pressure to sell. While the deep engagement with political struggle and calls for revolution that we see in the Liberation Art movement was unique to Palestine up until recently, its intersecting with the political sphere and spurring of artist-run initiatives is something that can be found in most modern national histories of the Arab world. Today, as we are witnessing a surge in activism across the Middle East and North Africa, how might we reconcile an art scene that is increasingly reliant on official sponsorship and private funding and heavily focused on appeasing collectors? In your opinion and in relation to your own experiences, can the two coexist?

SH: Remember that everything is in motion. Capitalism was once revolutionary but is now rotten. It is time for a new fruit. We need to live and so we take a job with a capitalist no matter how rotten the times. We have to. But we know that when revolution comes it changes most of us. We know that only the working class has the power to overthrow capitalists and they are in each and every corner of the world. So yes, the two can and do coexist everywhere. The question is, who has power over the other? Will sponsorship and private funding dictate to artists their content or will artists inspired by revolution select content and remain true?

[Samia Halaby working on “For Niihau from Palestine” (1985), a mural dedicated to “the liberation of the original Hawaiians.”]

MF: It is interesting to note that in your own curating of Palestinian art in the US, you maintained an open, collectively engaged method of working with your colleagues. With the 2002 exhibition “Williamsburg Bridges Palestine,” you and your co-curator, Lebanese artist Zena El-Khalil, made a point of accepting virtually every submission you received, from young, emerging artists to long established figures. Every medium was accepted, as were many forms of representation. In the end there were fifty artists included in the show. Has it been a conscious decision to honor the informal networking of the Liberation Art movement in regard to fostering an environment in which artists can contribute freely without worrying about bureaucratic art world hierarchies and gatekeeping?

SH: The short answer is yes, and we received a lot of criticism for it. Some people wanted us to make shows of only a few artists and make them—what shall I say? Slick. But I maintained that the audience has the right to select their favorites and it is unfair to impose on them the tastes of the curators who are selected from above, so to speak. I discovered that it made for a lot more fun and discussion. I also discovered that there was not one single artwork that did not find a lover. After all, we all have friends and each piece found at least one friend and probably more. So each member of the audience deserves to enjoy the process of discovery, to be challenged, to think and examine and look, not just absorb what they are told is good art.

MF: When writing Liberation Art who was your intended audience?

SH: The audience is always the future to whom one has to speak the truth. In essence, I think less of my audience than I do of the importance of scholarship, investigation, understanding, and good analysis. I want to study what is there, analyze it and then state my findings. All this needs to be done within the larger picture of the history of global art. In this work, a work of history, rigorous scholarship is more important than focusing on an audience. At the same time, I think one has to respect the audience, put their knowledge out there and let it be judged worthy or unworthy—anything less is cowardice.